From the India Today archives (1983) | Non-aligned Movement: When India took charge

The atmosphere of expectancy was fuelled by collective relief that the reins of NAM had finally passed from Cuba to India

(NOTE: This is a reprint of a story that was published in the INDIA TODAY edition dated March 31, 1983)

(NOTE: This is a reprint of a story that was published in the INDIA TODAY edition dated March 31, 1983)

From the moment the opening chords of the Non-aligned orchestra’s seventh performance in New Delhi last fortnight drifted across Vigyan Bhavan, it was already obvious that this was to be no ordinary summit. Long before the representatives of 101 countries, including 60 heads of state and government representing two-thirds of humanity—the largest ever such gathering in history—started deplaning at the spruced-up arrival area at Palam Airport the atmosphere was charged with expectancy.

The expectancy was undeniably fuelled by a collective air of relief that the reins of the Non-aligned Movement (NAM) had finally passed from Cuba to India, thus ending a highly controversial and questionable 42-month period in the movement’s history; a period that saw increasingly sharp divisions within the movement as well as a tragic loss of credibility. But more than the relief was the unquestionable realisation that India intended to take charge of the movement with uncustomary authority.

Decisive air: Right from the moment that Mrs Gandhi, in her new role as chairman (or rather, chairperson as she herself directed she be termed) of the movement ascended the rough-hewn speaker’s podium and slipped on her elegant spectacles to deliver her keynote speech, there was evident a no-nonsense air and decisiveness in her movements which clearly spelt out the message that India had taken charge.

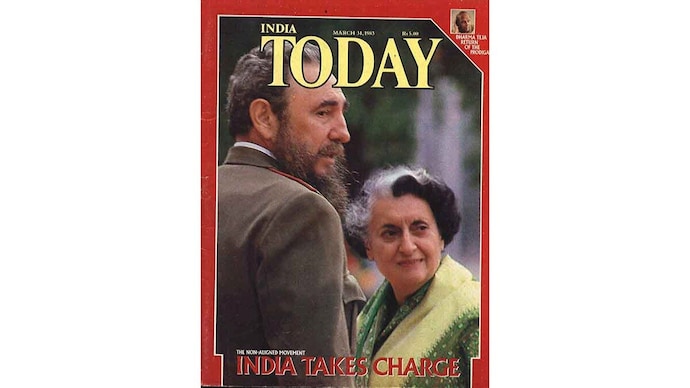

And finally, when she returned to her seat in the Centre of the velvet-draped dais, there was far more than mere symbolism in what turned out to be the most-photographed event of the summit—the warm, affectionate embrace that outgoing chairman Fidel Castro gave her after pointedly ignoring her outstretched hand. In that highly-charged moment, with the tiny figure of Mrs Gandhi draped in green and gold enveloped in the olive-green uniform of the bearded Cuban leader, lay the fragile future of the movement for the next few years; a future that would largely be governed, and guided, by Mrs Gandhi’s moves and initiatives.

If Mrs Gandhi’s initial actions are any indication, she is clearly determined to shake the movement out of its lethargy, NAM, described by the new chairperson as “history’s biggest peace movement”, has never been more in need of rejuvenation and recharging of its batteries. The Havana summit, in 1979, brought the movement to a lurching halt and the political and economic pressures of the last 42 months proved too much, even for Castro’s broad shoulders.

Now, with Mrs Gandhi at the helm, there is obviously a new awakening, a new optimism and a new sense of purpose. As Professor G.L. Bondarevsky one of the three Soviet experts on non-alignment and international relations in New Delhi during the summit, predicted: “The seventh summit will be the most crucial in the history of the movement. You now have the right lady at the right place and the right time.”

Appreciation: Bondarevsky’s statement was echoed faithfully by every one of the 110 speakers who addressed the summit during the six-day deliberations, and a majority of them undoubtedly meant it. Singapore’s crusty Deputy Prime Minister S. Rajaratnam, who created a storm when he roundly criticised the movement’s “growing impotency”, later told India Today that New Delhi had injected a breath of fresh air into the movement. “We are now assured of strict impartiality,” he remarked, “if anything objectionable happens, there will be no question of the chairman having fixed it,” a snide reference to former chairman Castro’s controversial decision to keep the Kampuchean seat vacant during the Havana summit.

But it was also an unspoken acknowledgement that the movement was now in capable hands and nobody could have demonstrated the truth of that more than Mrs Gandhi herself. If her stamina was characteristic before the summit, by the time it ended it was legendary. Except for the average of four hours’ sleep she gave herself each day in the early morning hours, Mrs Gandhi was constantly on the move, maintaining the pressure and momentum that had started last November with what was India’s most concerted diplomatic blitz ever. Midway through the summit, one Indonesian delegate was moved to marvel aloud: “It looks like Mrs Gandhi has a 36-hour day”; a tribute to her hectic, non-stop schedule which included meetings in her makeshift office at Vigyan Bhavan with a string of heads of state, chairing the conference and attending to her prime ministerial duties.

And yet, it will take more than mere stamina if India is to earn a permanent niche in the movement’s history. As last fortnight’s events revealed, each NAM summit also serves to reopen old wounds, bring divisions into sharper focus and unearth bones of contention that may have been long buried. Not unpredictably, the pre-summit deliberations by non-aligned foreign ministers chaired by Indian Foreign Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, was dominated by the contentious Kampuchean issue which stretched into a marathon debate lasting almost the entire three days.

Contentious issue: Ultimately, the issue proved a Gordian knot that even India’s diplomatic offensive and frantic backstage lobbying failed to untie. While a total of 36 countries spearheaded by the Association of South-east Asian Nations (ASEAN) forcibly moved to give the vacant seat to the Sihanouk-led coalition government, 31 countries strongly opposed the move in support of the Heng Samrin regime. In that situation, the only choice before Rao was to pass the buck on by sticking with the Havana decision and leaving the issue open. Rao’s task was made more difficult by the fact that India supports the Heng Samrin regime and any effort to sway the deliberations would have cast immediate doubts on India’s credibility.

In return for leaving the issue open and the Kampuchean seat vacant, the ASEAN-led group demanded, and received, an agreement that clear-cut criteria would be established by NAM for the future expulsion or suspension of a member state. In fact, the original 23-page Indian draft declaration, circulated to all members of the movement at the beginning of February, had called for a “comprehensive political solution which would provide for the withdrawal of all foreign forces” in Kampuchea. It also urged all states in the region to “undertake a dialogue which would lead to the resolution of differences among themselves and the establishment of durable peace and stability in the area”.

The Kampuchean crisis offered, however, the classic non-aligned contradiction of one of their member states becoming a battleground of superpower rivalry and the pulls and pressures that result. The ASEAN countries like Singapore were obviously dancing to the Sino-American tune of denigrating the Soviet-backed Heng Samrin regime as propped up by the Vietnamese army and questioning its legitimacy. The Soviets, through Vietnam and Laos, sought to dismiss the claims of the Sihanouk regime on the grounds that they had no physical control of the country and they were guilty by association of the brutal crimes of the Pol Pot regime and the Khmer Rouge which is part of the Sihanouk coalition.

Consensus decision: But by the end of the summit, a major breakthrough had been made with three ASEAN members and Vietnam and Laos finally agreeing to find a settlement through negotiations amongst themselves without intervention by any external power, including China. Rajaratnam himself confirmed that the idea of a “collective dialogue” had taken shape in the corridors of Vigyan Bhavan thanks to two major Vietnamese concessions the Heng Samrin regime in Kampuchea need not be present and that the dialogue be held without preconditions.

But if New Delhi failed to finally resolve the Kampuchean question, the Indian side at least succeeded in ensuring that the issue did not serve to stall proceedings during the actual summit. Many heads of state were politely pressured to play down the Kampuchean issue during their speeches or at least avoid outright support to one side or the other. One leader who complied was Pakistan’s President Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq. In his speech, circulated in a glossy green folder, one paragraph on Kampuchea has been carefully whitened out in what was obviously a last-minute concession.

Diplomatic feat: The deleted portion reads: “The United Nations has duly recognised the coalition government of Democratic Kampuchea as the legal representative of the people of Kampuchea. The Non-aligned Movement would be wanting in the fulfilment of its fundamental obligation if it were to adopt a position at variance with that of the international community by not permitting the legitimate Government of Democratic Kampuchea to assume its rightful seat in the movement.” Pakistan’s support for the Sihanouk faction is well known and it must have taken considerable persuasion to make Zia leave out the portion he did.

But India’s moderating influence failed to stop the Kampuchean issue from degenerating into a propaganda battle outside the summit confines. The Singapore delegation, still smarting at Castro’s handling of the Kampuchean issue in Havana, circulated a hard-hitting indictment of Cuba’s chairmanship entitled “Havana to New Delhi: What has it achieved?” which spoke in combatitive terms of the “swamp” and “brothel area” that Cuba had led the movement into.

Cuba lost no time in circulating its equally-acid reply titled “From Singapore to Singapore” claiming that the US State Department had sent detailed instructions to a number of non-aligned states on the kind of stand they should adopt in New Delhi. “Singapore.” said the document, “aspires to be the Troy Horse (sic) of imperialism within the movement and the broadcast of the Voice of America with a Chinese accent.” In a later interview, Singapore’s Rajaratnam described the Havana Summit as having “Castroated” the movement.

Verbal battleground: Cuba and Singapore were not the only culprits. Half-way through the summit, the crowded media centre in Vigyan Bhavan became a verbal battleground with propaganda pamphlets littering the shelves like confetti. But eventually, they also served to indicate in advance the issues that would prove the most intractable of which the Iran-Iraq war and the related decision of where to hold the next NAM summit predictably raised the most dust. These also succeeded in extending the summit well beyond its appointed deadline.

India had made a Herculean effort to hammer out some kind of a peace settlement between Iran and Iraq which, if it worked, would have been the biggest breakthrough in the movement’s 21-year-old history. Both the Indian ambassadors in Baghdad and Teheran had been summoned back for the meeting to aid in the closed-doorconsultations with the two warring countries and Mrs Gandhi had made an emotional appeal on the subject during her keynote address at the inaugural session. But clearly the Iranian attitude during the summit and in their press briefings displayed that they were in no mood for compromise. Both sides had kicked up a controversy even before the summit started, by flying in heavily-armed commandos without informing the host country about their intentions. Iraq President Saddam Hussein kept the summit in suspense till the last minute before finally deciding not to attend.

Even without his presence, the contrast in the attitudes of both sides was an overt indication of their respective positions. The Iraqis, clad in sober suits and ties, maintained a low profile throughout, which was in keeping with their avowed decision to put an end to the fratricidal war. They were clearly prepared to bend over backwards in their efforts to bring peace and some semblance of economic stability to the region. The Iranians, sporting the scraggy beards that have become a badge of their revolution, displayed the kind of arrogance that can only come with fanatical faith in a divine cause.

It must, however, be said to the credit of the Indian negotiators that they succeeded in getting the Iranians to climb down from their condition that the removal of Saddam Hussein was a prerequisite for ending the war. But Iranian Prime Minister Hussein Moussani-Khamanei made it appallingly clear that the other conditions: withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Iranian territory; payment of reparations amounting to S50 billion; the naming of Iraq as the aggressor; and the return of Iraqi exiles in Iran would remain. Even Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak’s major diplomatic initiative during the summit to mediate between the two warring camps failed to mellow the Iranian stand.

Commendable effort: Inevitably, the Iran-Iraq issue and the related question of the venue of the next summit, which was overwhelmingly in favour of Baghdad, stretched proceedings beyond the scheduled deadline. In a final and Herculean effort to break the deadlock, Mrs Gandhi called in the heads of both delegations shortly after midnight on the last day to try and hammer out an acceptable compromise, PLO leader Arafat was also requisitioned to use his not inconsiderable influence on the two sides.

At 1.15 a.m. a beaming Mrs Gandhi returned to the main hall to announce that the compromise had been reached on the draft declaration which, with relatively minor changes and the deletion of one paragraph (at the insistence of Iran) was more or less the same as the original draft submitted by India. But even the brief two paragraphs on the two issues that held the key to the success and failure of the summit represented a major triumph not just for Mrs Gandhi but for the movement.

And, even though the summit failed to bring a guarantee of peace between Iran and Iraq, its achievements in regard to the general crisis in the Middle East were not entirely insignificant. As Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Saud-al Faisal sagely observed: “For the first time in several years, the Arab countries have put up a solid front.”

Interim understanding: An imprecise measure of understanding was reached between PLO leader Yasser Arafat, the most ebullient presence at the summit, and King Hussein of Jordan, as well as between Arafat and President Gemayel of Lebanon on the complex Palestinian issue. The fact that the original Indian political draft had finally been expanded from 23 pages to its final 92-page format was largely because of the extra paragraphs that Arafat insisted on inserting. The original draft on Palestine contained five paragraphs, the final draft contained 17.

Further, the Fez Peace Plan was approved by all the Arab leaders present, including Arafat, while the Reagan Peace Plan was rudely sidelined for the absurdly simple reason that nobody was really convinced that Reagan could force Israel to allow a Palestinian homeland to flower on the West Bank and Gaza, even if it was not officially declared as a sovereign state.

But by far the biggest triumph of India’s shuttle diplomacy during the run-up to the summit was over the prickly Afghanistan issue. As in the case of Iran and Iraq, the Indian Ambassador in Kabul, Mani Dixit was flown back to New Delhi for the summit. Clearly, the pre-summit negotiations had succeeded in ensuring, that the issue was kept as muted as possible, particularly in the case of Pakistan. Zia has already established a hot line to Moscow over the Afghanistan question and as he himself remarked: “The key to open the door to the Afghanistan issue lies in Moscow and we must realise that.”

Afghanistan Prime Minister Sultan Ali Keshtmand, widely tipped to take over from Babrak Karmal shortly, took a predictable line in his speech praising the Soviets for their help and support of the Non-aligned Movement. But both Pakistan and Afghanistan stand to gain considerably from the constructive turn the Afghan crisis took during the summit. The ongoing negotiations have led to a situation where Pakistan, and consequently the rest of the world, will recognise the Karmal regime. In return, Pakistan will agree to the Durand Line being recognised as the international frontier.

In fact, one major success of the deliberations over the Afghanistan issue was almost immediately apparent. On his return to Dhaka after the summit. Bangladesh Chief Martial Law Administrator H.M. Ershad announced that his country had decided to normalise relations with Kabul. Ershad stated that his talks in New Delhi during the summit with Keshtmand had been a success and had brought about a measure of understanding between the two countries.

But throughout the hectic lobbying activity in the corridors and private rooms, and the intense football huddles in the main hall, it was clear that what the entire exercise boiled down to in the final draft was a tricky tightrope walk between the two countries that were conspicuously absent - the superpowers. Nothing perhaps demonstrated this as much as the manoeuvring over the final declaration on the Indian Ocean. The original draft covered five paragraphs which contained a pointed reference to the American base on Diego Garcia, now in the process of undergoing major expansion. However, Sri Lanka, which hosts a conference on the Indian Ocean next year in Colombo, was eager that the US be represented at the conference. Accordingly, Sri Lanka, which had done its homework well, moved an amendment in the early stages of the summit to delink the Diego Garcia issue from the declaration on the Indian Ocean.

The strategy was clearly to avoid irritating the US which could have led to their refusal to attend the Sri Lanka conference. Despite efforts by India and front-line African states to stick to the original formulation, Sri Lankan diplomacy triumphed. The final draft contains no mention of Diego Garcia in the section on the Indian Ocean but refers to it as “foreign bases”, while a separate section titled ‘Mauritian Sovereignty over Chagos Archipelago. including Diego Garcia’ has been added on to the final declaration.

Soviet discomfiture: But if the Indian Ocean declaration represented a minor victory for the US it was clearly a defeat for the Soviets. To Moscow’s discomfiture, the formulation on the Indian Ocean equated the USSR with the US in terms of military presence in the area. But the Soviets could have gained scant consolation from the fact that overall, the final draft contained more of an anti-US edge than an anti-Soviet one - the US was criticised by name 15 times though it was obvious that the summit was in no mood to confront either head-on.

No socialist member of NAM raised the “natural ally” theory which proved so divisive at Havana. Compared to 15 speakers who praised the USSR for its efforts to arrest the nuclear drift and its support for liberation movements, even the staunchest pro-US members were unable to sing the praises of US foreign policy, including Singapore and Saudi Arabia. Among the middle powers, Britain came in for criticism while France received praise for its contribution towards resolving issues in the developing world.

Taking the political and economic resolutions together, the world outlook of NAM continues to remain pointedly anti-American - particularly among the Latin American countries - on nuclear weapons, militarisation, its backing of Israel and South Africa, disarmament and practically all economic issues involving the North and South. China, with its low-key diplomacy and low-profile presence outside the summit hall, escaped virtually unscathed. In the African context as well, the summit rejected the US Government’s view that Namibia’s independence was linked to the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola.

While NAM’s political discussions raised the most dust - and grabbed the largest headlines - there was much less rancour and more serious work under way in the economic committees. The seventh summit, for a change, decided to tackle issues head on instead of leaving them simply at the declaration level. Calling for global negotiations at the earliest - the first conference as early as next year - the summit threw up two options, leaving it to Mrs Gandhi in her capacity as chairperson of the movement to choose one or the other. Sri Lanka’s President Junius Jayawardene said that India should call a meeting of selected heads of state, a sort of Third World Cancun-type initiative, to talk to the leaders of major developing countries to tackle the worsening global economy “by adopting a programme of immediate measures in areas of critical importance to developing countries”. The Algerian delegation put forward a separate idea that the non-aligned should assemble a committee of foreign ministers from amongst themselves to travel to the industrial nations and explain what the developing world is asking for.

The Algerians were being realistic in calling for an immediate dialogue with the rich nations. With rising unemployment, slower economic growth, higher inflation rates and generally sluggish trade, the world economy is currently in a tighter spot than at any time since the end of the Second World War and the crisis has hit the developed countries, which have tightened their purse-strings, no less than the developing world. It was for this reason that the Algerians sought and obtained from NAM, a division of the economic demands into two: an immediate programme of action and a longer perspective on starting global negotiations which will obviously take time to achieve.

Doubtful efficacy: There is no guarantee, of course, that the immediate demands will be met. They aren’t new, nor are the industrial countries in a relenting mood. Whatever clout the Third World had from its command of world oil has been frittered away by bickering among oil exporters and the steep fall in oil prices. Yet to emphasise their immediate demands, the conference asked specifically for:

* An increase in official aid to 0.7 per cent of the GNP of industrial countries, a target laid down more than a decade ago but still unachieved;

* Urgent action to ward off unmanageable foreign exchange debts among developing countries;

* Increased quotas and resources from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and less stringent conditions in making them available to developing countries;

* A substantial increase in World Bank lending programmes and more resources for the World Bank;

* Easier access for developing country exports into industrial nations; and

* More money for energy development and food production.

The Indian draft on the subject avoided mention of these immediate goals, preferring instead to leave the whole business of economic change to summit-level global negotiations. The Indian view was that the industrial nations would simply decline to consider such proposals saying that they would be discussed at the global negotiations anyway. But the contrary view prevailed, which wanted to safeguard immediate requirements without waiting for discussions which may or may not get off the ground quickly enough.

If there was any area of disappointment. it was in NAM’s efforts to promote economic cooperation among developing countries. South-South cooperation, as it is known in the jargon of international conferences, has consistently failed to take proper shape because the oil exporters have steadfastly refused to finance it, fund like the one set up by Kuwait and Saudi Arabia for promoting projects in developing countries, have merely dabbled in token programmes of a few hundred million dollars-a mere fraction of their overall oil surpluses of several hundred billion dollars, most of which is invested in the West. Confronted with demands for concessional aid in the past. OPEC countries were liable to try and hedge, calling for studies and investigations. At New Delhi, with Saudi Arabia firmly in charge, they were categorical in their response: with oil prices having tumbled by a quarter, OPEC surpluses have shrunk so much that there could be no question of OPEC-funded development banks or more low interest aid to fellow NAM members.

Possible breakthrough: Yet, NAM brought forward the germ of an idea which, if it catches on could begin to dwarf the more conventional problems. Seminal ideas generally need long periods of gestation and progress is often counted in decades. The very first summit in Belgrade in 1961 gave rise to the United Nations’ Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) which is holding its seventh meeting in Belgrade this summer. Ten years ago at Algiers, the movement initiated the idea of a New International Economic Order (NIEO). Though it has yet to be achieved, the demand for NIEO has spawned a series of discussions and results.

At New Delhi, the cry has gone out for a “new, equitable and universal international monetary system” which, the final declaration says, “would put an end to the dominance of certain reserve currencies, guarantee developing countries a role in decision-making, while ensuring monetary and financial discipline in the developed countries and preferential treatment for developing countries”.

What the New Delhi economic declaration called for was a radical transformation of the 40-year-old economic system which came off the drawing boards at Bretton Woods in the US in the last months of the Second World War - a time, as the declaration says - “when economic and political conditions were vastly different and only a few developing countries were sovereign, independent nations” and “the developing countries had an inadequate share of decision-making.... “ The new structure, which hasn’t been spelt out, would end the dominance of the dollar and a handful of currencies in world trade, sharp exchange rate fluctuations and the dependence of developing countries on the developed. It would give Third World multitudes a voice in global economic affairs.

Balanced conclusions: In the final analysis, what the summit achieved was to keep NAM basically anti-imperialist; detached it from its “spiritual closeness” to the USSR without depreciating Moscow’s contributions to the decolonisation processes; held the USSR no less responsible for the arms race than the US; nudged the Afghan and Kampuchean crises considerably closer to a political settlement; brought the Arabs closer together, at least for the moment: increased the prospects of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) being able to hold its twice disrupted summit, and sought to mobilise - with what success remains to be seen - the developing nations on a platform of collective self-help, self-sufficiency and in their economic bargaining with the North.

As Newsweek commented, the bulk of the final document was devoted to the five D’s - decolonisation, development, disarmament, detente, and democratisation (freedom from superpower interference) - the watchwords of the movement. But viewed in perspective, the final draft and the hard bargaining that had gone into it, represented an impressive list of positive results for a movement whose epitaph has been written on many a tombstone years ago. If the industrialised Western bloc has all along considered NAM a beggar’s opera with a cast of milling millions, the strident symphony raised at New Delhi clearly indicated that they can no longer turn a deaf ear.

Most observers of the movement are convinced that NAM has arrived at the crossroads. Whether it takes the high road or the low one largely depends on one person - Mrs Indira Gandhi. As she herself commented in her final speech at the end of the summit: “If you have selected me as the locomotive to pull the non-aligned train along, I will ensure that it does not go off the rails.” But it will take all her diplomatic skill and political acumen to wrestle the movement onto its desired course.

Dealing with squabbling factions in her domestic role is child’s play compared to the ruffled feathers she will have to smoothen in her new international role as head of history’s largest movement. And yet, viewed against the array of state heads present at the summit, Mrs Gandhi undoubtedly retained the most stature, a stature that will grow correspondingly with the kind of moves she makes as head of NAM.

For all the flamboyant displays of Arafat and Castro linking hands and flashing the “V” sign, the bitterness of the Iran-Iraq enmity and the Kampuchean question, if the summit proved anything it was the degree and desire of conciliation. In the intimate atmosphere of a summit like last fortnight’s, the pressure to sink differences and the motivation to find ways out of intractable issues is a tangible force that, in a world riven by rivalry and war, represents NAM’s biggest asset as well as its potential global clout. An objective head count showed that NAM’s inner strength, and Mrs Gandhi’s now, lies in the growing number of moderates who people the movement. Mrs Gandhi’s place in history is already assured but if she can mould the movement into what its principles and its original founders envisioned, the writing of that history will be considerably ennobled.

—With Bhabani Sen Gupta

Subscribe to India Today Magazine